Return to Articles / Essays

Reflections at Fifty.

Published in Canadian Notes and Queries, Number 100.

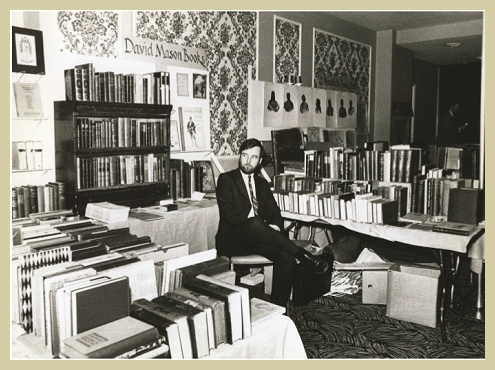

It might be nice if this title meant that I was going to meditate on turning fifty years of age but, unfortunately, it’s about being fifty years a bookseller, an anniversary I will have reached this year, on June 15, just after lunch to be precise.

I’m constantly amazed that I have actually lived this long, given the excesses of my youth—eight years sleeping in fields and under bridges in Europe, then many years drinking and smoking too much—but here I am. And not only am I still around, I’m having the time of my life. Books have not only saved my life innumerable times—as I never get tired of stating—but they have provided me, quite aside from the enormous gifts of their contents, not only with my living (such as it’s been) but an enormous amount of pleasure and excitement while they did so. And I mustn’t fail to mention that the book culture brought me my partner, the “renowned Canadian rare book dealer” Debra Dearlove (as a prominent industry publication has called her), but also the majority of my friends and acquaintances—writers, publishers, editors, journalists, agents—and most important, collectors and other devoted readers like myself. My oldest friend, Alfred Ames, who I met when we were both kids working at an insurance company, our friendship formed because we both were incessant readers, and with whom I shared so many adventures (Europe, drugs, marriages, children, disasters, triumphs), is still a close friend, and now, in our old age, we still meet for dinner often, to discuss our rich pasts and life and where it’s taken us. And still we exchange books and discuss our reading.

I’m constantly amazed that I have actually lived this long, given the excesses of my youth—eight years sleeping in fields and under bridges in Europe, then many years drinking and smoking too much—but here I am. And not only am I still around, I’m having the time of my life. Books have not only saved my life innumerable times—as I never get tired of stating—but they have provided me, quite aside from the enormous gifts of their contents, not only with my living (such as it’s been) but an enormous amount of pleasure and excitement while they did so. And I mustn’t fail to mention that the book culture brought me my partner, the “renowned Canadian rare book dealer” Debra Dearlove (as a prominent industry publication has called her), but also the majority of my friends and acquaintances—writers, publishers, editors, journalists, agents—and most important, collectors and other devoted readers like myself. My oldest friend, Alfred Ames, who I met when we were both kids working at an insurance company, our friendship formed because we both were incessant readers, and with whom I shared so many adventures (Europe, drugs, marriages, children, disasters, triumphs), is still a close friend, and now, in our old age, we still meet for dinner often, to discuss our rich pasts and life and where it’s taken us. And still we exchange books and discuss our reading.

In the mid-nineties, by a weird fluke, I gave a talk on my so-called career, a fluke compounded by having a friend in the audience who edited a magazine and decided she would publish it. This led to other talks and other publications, so that in late middle-age—never having ever contemplated writing, never even having written that self-pitying romantic poetry that all my friends did in their teens—I found myself scribbling away. This new passion interfered with business interests to the great irritation of Debra Dearlove, who was more interested in surviving than watching me write drivel.

Then John Metcalf bullied me into attempting a memoir, to which my first response was, “I could never fill a book.” Then I filled two, necessitating some severe editing. It was through the dredging of my memory that I began to grasp the extent and depth of all the adventures that provided so many anecdotes for the book. And it was during those explorations of my past that I came to realize how enormously lucky I’ve been to be a book reader all my life, and a bookseller for fifty years. And how much books have enriched me.

So lucky have I been, that when I contemplate it all, I shudder with horror at how easily I could have detoured onto so many other paths, all leading to doom and destruction. I am not unaware that much of what I say is so clichéd that it might be more appropriate for The Reader’s Digest than CNQ, but it can’t be helped. It’s all true. And it’s for this reason that I constantly preach to the young the mantra my conservative banker father told me as a youth. It was the only philosophic axiom he ever offered me, but what an important one! “Try and find some work to do that you can love,” he said, “And then do it as best you can.” Was he ever right. Banking didn’t ruin his soul but I have come to believe that his wonderful advice came from the bitter realization that he did not love his own work and that he wanted his son to obtain what he’d missed. If that’s true, and if he could see me now, he would surely be happy that his son got what he’d learned was more important than respectability and security.

And there are complexities which make his axiom seem even more significant for me.

Imagine discovering bookselling at almost thirty, having failed at everything I’d tried till then. Not even a grade nine education, almost ten years bumming around North America, Europe, and North Africa, digging ditches and washing dishes, hustling to stay alive. Amongst the earliest refugees from the deadly dull post-war conformity of the North American 1950s—following the Beats and anticipating the Hippies— part of the reactive surge that exploded into the sixties, changing everything. And much of it for the better in spite of what they say now. But for me, all through the drugs and the insanities and the deaths, books and reading were my guides and, ultimately, my saviours. Books have not only saved my life several times, they have enriched it in ways I couldn’t have conceived of in the beginning.

When I began as a bookseller, already a lifelong reader, I had long entertained the concept that I had been born knowing how to read, for I had no recollection of learning, nor of a time when it wasn’t my great passion. There were a few clues, discernable as such only years afterwards. Were my early attempts to con my mother into thinking I was too ill for school so I could stay home and read part of the same character trait that got me expelled from school at fifteen so I could educate myself through reading? And surely it’s the same trait that, in spite of my increased sociability as I age, makes me treasure solitude, a state that remains central to my whole being? A love of solitude, the preference to be alone, either immersed in my own thoughts or engaged in the dreams and ideas provided by the author I’m reading is still as necessary to me as food and sleep. The anticipation and excitement of carrying home a newly acquired book is the same to me at seventy-seven as it was at seven. Oh, the magic, the magic… the wonder of it.

It all becomes clearer on reflection. But what remains most clear is that the essence is in the reading, which explains why I love to give books to people, especially children. All my friend’s children, and the kids on my street, get books. I wonder if I’m the only person anywhere who gives out books with candy on Halloween? You can get nice Halloween books at the dollar store and Halloween popups and light-ups on the remainder tables…

It is surely an attempt to pass it on, this wonderful, unending gift. I work on the principle that if I make one child in a thousand a reader I have done my duty. That we can never know how our efforts will play out twenty to forty years down the line, whether they’ll ultimately be futile, means only that we should retain our optimism and keep trying. “Right action” it’s called, and of course I learned the truth of that in a book—the Bhagavad Gita to be precise—over fifty years ago. That principle still holds, I know because I’ve used it for all these years.

So, I have been lucky enough to have lived a long life and, like many others, one full of small triumphs and not-so-small failures, costly errors of judgement and profitable ideas, ups and downs, in love and friendship— and hope and despair in all those things. Like everyone else; but in my case I was sustained through it all by my vocation. Books added to my passions and visions. Even through the down periods, the crushing blows, they always offered examples, gave meaning to everything.

Reading has also been my entertainment, my relief from work and everything else. Whatever the outside pressures, I could always pick up a book and instantly be in another world. And I could stay there until I was rejuvenated and could remerge, strong again, ready to go on with new insights and ideas stolen from my betters, from those who came before. I think often and with great pleasure of a poster once seen in a children’s bookstore. An open book, a child in mid-air between the leaves, it read: “A book opens and you fall in.” So true, and not just for kids. Only books provide that complete transformation.

I did not understand then that without books I might have died from my heavy drinking, or any of the many perilous situations heavy drinking brings with it, as so many of my friends and acquaintances did…

And I certainly could never have known in the beginning the many things that would come from buying and selling books. I have probably handled millions of books, sorting, observing, judging, seeking the important and the curious and much of the detail from that process has been absorbed and become part of me, given me instincts and conferred knowledge unknown to the average reader.

Working for the Pope gave me a love of bindings (yes, you can judge a book by its cover —sometimes) and the pleasure that comes from learning the sophisticated methods used for hundreds of years to protect the sacred text. It all started with the simple protective covers the binders put on the first printed books in the fifteenth century, which were often exquisitely blindstamped with designs and symbols. Those early bindings are studied seriously now, to the point that experts can determine the styles of particular binders known to posterity only by their association with the rich patrons who commissioned them and now refer to them as “the binder of so and so”. Some people, and I am one of them, pay thousands of dollars to commission modern designs from binders who are true artists, and who, since their names are known, can receive the acclaim their talents deserve.

I came late to book illustration but am now fascinated with all aspects of it, from the simple woodcut to the sophisticated modern colour techniques, with the sequences of other techniques between, from engraving to lithography, and hand-colouring. In Victorian times, this was often done exquisitely by nineyear-old girls working in factories for sixteen hour days —a cruel indictment of human greed and lack of imagination, though it resulted in objects of great beauty, confounding our moral dilemmas even more. Everything led to our present, sophisticated means of printing colour. And the designing of books to which many people, mostly unknown to the innocent reader, have devoted their entire lives.

Few people know—and probably less care—that throughout the world small groups of aficionados devote all their free time to gouging out wood and linoleum so they can stamp pictures for their own pleasure (some actually make a living from it, but most are passionate amateurs). Others labour all night setting handtype to print, with hand-presses, some poem or saying they love, finishing with their hands and faces filthy with ink, in order to produce a single beautiful sheet with words or pictures, of no interest or use to anyone but themselves and their equally deranged friends. Everywhere there are these little groups of seemingly demented people making and worshipping the results of their passions, seeking to realize the beautiful visions their imaginations have shown them. About William Blake, obsessed with things no one else could see, his wife famously said, “I do not have much of the company of Mr. Blake. He is always in paradise.” Thought to be a lunatic then, now seen as a genius, one of the holy ones. And always, the books; first the inspiration, then attempts to inspire others; pass it on, pass it on. The wonder of it, the thrill.

And books continually offer new things, unexpected things, like looking at a woman you’ve seen a hundred times and one day seeing her in an entirely new way and falling in love. So I have done with books, I continually notice new things in familiar, previously ignored areas and the next thing I know I’m working on yet another new collection.

Early paperbacks seduced me with their wonderful, clever, commercial art—I tend to seek those that I read as a sex- and adventure-obsessed teenager in the fifties. I’ve built a collection based on the familiar, sentimental nostalgia these books induce, warm memories of my innocent naiveté (all those years ago). This went from a curious interest to a passion, then an obsession, each stage conferring increased sophistication, the parameters always widening, while more and more money was spent, with assurances to Debbie that she will make enormous profits in a few years due to my astute foresight (and she will, too).

Then postcards. After laughing for years at the silly people at flea markets and paper shows who sit for hours flipping through shoeboxes of postcards, searching for their particular passion, counties, towns, sometimes subjects, I succumbed as well. Occasionally, I would look casually for scenes from one particular place and one historical subject of personal interest, but one day, browsing, I noticed the cards that no one collects or seems to look at, the cards for the festivals—Christmas, New Year’s, and Easter—and I saw, on close examination, that those from the 1890s to 1920s or so were stunning examples of elaborate colour printing; printing far more beautiful and sophisticated than anything we see today. I began slowly buying, graduating from 25 cents and 50 cents each to $2 and $5, then buying whole albums by negotiating to get even lower individual prices. New subtleties, previously unnoticed, widened by my focus until I was buying hundreds of them knowing that, like everything one sees at flea markets, they will soon become noticeably scarce and then disappear into rarity. One day they will be worth twenty, fifty times what they are now. So goes scouting with the sophisticated scout who has the eye and the imagination to see new possibilities in ignored treasures.

“I ransack libraries and find them full of sunk treasures,” said Virginia Woolf.

Every bookseller and everyone who frequents used bookstores knows the truth of Woolf’s discoveries, for we are immersed daily in the leavings of the past and have much experience in the serendipitous discoveries awaiting anyone with a sharp eye in every bookshop.

Dealers and collectors scouting bookshops know that books can be treasures for those who can recognize the things which make a book valuable quite aside from the text. For that you need “The Eye”, the skills that all scouts nurture over many years. The great book collector Michael Sadleir once said something I repeat to myself every time I enter a bookshop, “In nature the bird who gets up earliest catches the most worms, but in book collecting the prizes fall to birds who know worms when they see them.”

There are a thousand unpursued themes where applied intelligence and discrimination can turn dross into treasure. I can’t go anywhere without new ideas and themes tunneling into my consciousness; it never gets boring. If I had time and space I would build a huge fortune, and simply wait for the world to catch up. Of course, when I tell Debra Dearlove that, she rolls her eyes. “Perhaps you’re right,” I say—smiling inside to myself because I know I’m right. But the problem is I don’t have the space or the money— and I certainly don’t have the necessary time to see my visions realized. But that has always been the fate of the visionary, just as the derision and dismissal of the naysayers has been the visionary’s reward.

But all these things I tell—of which I have thousands more examples—are not the core of it. For over fifty years living with this wonderful result of becoming addicted to reading and books (and not to ignore the magnificent irony, that after a lifetime of grappling with deadly addictions, I exult another addiction: but this one offers life, not death), I have come to realize that the greatest pleasure in it all—aside from the reading—has been the people.

All those eccentric, or just strange, people, weird and wonderful, passionate but a bit crazed, brilliant but perhaps demented—all sharing the same urge, the obsessive search for the missing book, the Holy Grail of the scout, the prize we all knew was out there somewhere, waiting for us. In the end it has been my immersion in that universe of knowledge, arcana, stories, theories, systems, plans, all fueled by the fire consuming us, all from those books which fill our lives.

I have spent much of that fifty years mixing with people of such diversity that it fills me with awe. I know people, often colleagues, who can talk knowledgeably on any period of history and often in several languages; or aspects of the sciences, or the arts, on the levels of their greatest producers. I have seen brilliance, even genius. I have had conversations with people whose knowledge or sensibilities are so much more advanced or acute than mine that I have been humbled by my inferiority—except that the humanity of these people is such that they never seem to notice their superiority. I have also known people— and not a few –whose brilliance seemed inseparable from their craziness, but who so exhilarated me that I embraced both with equal gusto.

In my years of appraising people’s archives, I have witnessed the whole inner history of people who made me proud to be a human and associated, however marginally, with such superior intellects.

I have seen greatness up close, and more often than you might think, people who have actually changed the world. I have had days when it made me feel small and insignificant and days when it spurred me to stretch my own attempts past what I know to be my limits.

I could fill a book with the lessons I’ve learned from all those appraisals. Sometimes I have been brought to tears. And it is all really just a reflection of what we humans are capable of. In the end, what most remains is the pride, pride to have been a part of it all; this great experiment we are engaged in, of being human.

So, June 15, 1967, a day of miracles perhaps—certainly for this unbeliever—where in a few minutes a consummate failure became a passionate visionary with a noble mission. Who’s to say that one moment cannot change the world? What a run I’ve had, and all from books.

-David Mason

I’m constantly amazed that I have actually lived this long, given the excesses of my youth—eight years sleeping in fields and under bridges in Europe, then many years drinking and smoking too much—but here I am. And not only am I still around, I’m having the time of my life. Books have not only saved my life innumerable times—as I never get tired of stating—but they have provided me, quite aside from the enormous gifts of their contents, not only with my living (such as it’s been) but an enormous amount of pleasure and excitement while they did so. And I mustn’t fail to mention that the book culture brought me my partner, the “renowned Canadian rare book dealer” Debra Dearlove (as a prominent industry publication has called her), but also the majority of my friends and acquaintances—writers, publishers, editors, journalists, agents—and most important, collectors and other devoted readers like myself. My oldest friend, Alfred Ames, who I met when we were both kids working at an insurance company, our friendship formed because we both were incessant readers, and with whom I shared so many adventures (Europe, drugs, marriages, children, disasters, triumphs), is still a close friend, and now, in our old age, we still meet for dinner often, to discuss our rich pasts and life and where it’s taken us. And still we exchange books and discuss our reading.

I’m constantly amazed that I have actually lived this long, given the excesses of my youth—eight years sleeping in fields and under bridges in Europe, then many years drinking and smoking too much—but here I am. And not only am I still around, I’m having the time of my life. Books have not only saved my life innumerable times—as I never get tired of stating—but they have provided me, quite aside from the enormous gifts of their contents, not only with my living (such as it’s been) but an enormous amount of pleasure and excitement while they did so. And I mustn’t fail to mention that the book culture brought me my partner, the “renowned Canadian rare book dealer” Debra Dearlove (as a prominent industry publication has called her), but also the majority of my friends and acquaintances—writers, publishers, editors, journalists, agents—and most important, collectors and other devoted readers like myself. My oldest friend, Alfred Ames, who I met when we were both kids working at an insurance company, our friendship formed because we both were incessant readers, and with whom I shared so many adventures (Europe, drugs, marriages, children, disasters, triumphs), is still a close friend, and now, in our old age, we still meet for dinner often, to discuss our rich pasts and life and where it’s taken us. And still we exchange books and discuss our reading. In the mid-nineties, by a weird fluke, I gave a talk on my so-called career, a fluke compounded by having a friend in the audience who edited a magazine and decided she would publish it. This led to other talks and other publications, so that in late middle-age—never having ever contemplated writing, never even having written that self-pitying romantic poetry that all my friends did in their teens—I found myself scribbling away. This new passion interfered with business interests to the great irritation of Debra Dearlove, who was more interested in surviving than watching me write drivel.

Then John Metcalf bullied me into attempting a memoir, to which my first response was, “I could never fill a book.” Then I filled two, necessitating some severe editing. It was through the dredging of my memory that I began to grasp the extent and depth of all the adventures that provided so many anecdotes for the book. And it was during those explorations of my past that I came to realize how enormously lucky I’ve been to be a book reader all my life, and a bookseller for fifty years. And how much books have enriched me.

So lucky have I been, that when I contemplate it all, I shudder with horror at how easily I could have detoured onto so many other paths, all leading to doom and destruction. I am not unaware that much of what I say is so clichéd that it might be more appropriate for The Reader’s Digest than CNQ, but it can’t be helped. It’s all true. And it’s for this reason that I constantly preach to the young the mantra my conservative banker father told me as a youth. It was the only philosophic axiom he ever offered me, but what an important one! “Try and find some work to do that you can love,” he said, “And then do it as best you can.” Was he ever right. Banking didn’t ruin his soul but I have come to believe that his wonderful advice came from the bitter realization that he did not love his own work and that he wanted his son to obtain what he’d missed. If that’s true, and if he could see me now, he would surely be happy that his son got what he’d learned was more important than respectability and security.

And there are complexities which make his axiom seem even more significant for me.

Imagine discovering bookselling at almost thirty, having failed at everything I’d tried till then. Not even a grade nine education, almost ten years bumming around North America, Europe, and North Africa, digging ditches and washing dishes, hustling to stay alive. Amongst the earliest refugees from the deadly dull post-war conformity of the North American 1950s—following the Beats and anticipating the Hippies— part of the reactive surge that exploded into the sixties, changing everything. And much of it for the better in spite of what they say now. But for me, all through the drugs and the insanities and the deaths, books and reading were my guides and, ultimately, my saviours. Books have not only saved my life several times, they have enriched it in ways I couldn’t have conceived of in the beginning.

When I began as a bookseller, already a lifelong reader, I had long entertained the concept that I had been born knowing how to read, for I had no recollection of learning, nor of a time when it wasn’t my great passion. There were a few clues, discernable as such only years afterwards. Were my early attempts to con my mother into thinking I was too ill for school so I could stay home and read part of the same character trait that got me expelled from school at fifteen so I could educate myself through reading? And surely it’s the same trait that, in spite of my increased sociability as I age, makes me treasure solitude, a state that remains central to my whole being? A love of solitude, the preference to be alone, either immersed in my own thoughts or engaged in the dreams and ideas provided by the author I’m reading is still as necessary to me as food and sleep. The anticipation and excitement of carrying home a newly acquired book is the same to me at seventy-seven as it was at seven. Oh, the magic, the magic… the wonder of it.

It all becomes clearer on reflection. But what remains most clear is that the essence is in the reading, which explains why I love to give books to people, especially children. All my friend’s children, and the kids on my street, get books. I wonder if I’m the only person anywhere who gives out books with candy on Halloween? You can get nice Halloween books at the dollar store and Halloween popups and light-ups on the remainder tables…

It is surely an attempt to pass it on, this wonderful, unending gift. I work on the principle that if I make one child in a thousand a reader I have done my duty. That we can never know how our efforts will play out twenty to forty years down the line, whether they’ll ultimately be futile, means only that we should retain our optimism and keep trying. “Right action” it’s called, and of course I learned the truth of that in a book—the Bhagavad Gita to be precise—over fifty years ago. That principle still holds, I know because I’ve used it for all these years.

So, I have been lucky enough to have lived a long life and, like many others, one full of small triumphs and not-so-small failures, costly errors of judgement and profitable ideas, ups and downs, in love and friendship— and hope and despair in all those things. Like everyone else; but in my case I was sustained through it all by my vocation. Books added to my passions and visions. Even through the down periods, the crushing blows, they always offered examples, gave meaning to everything.

Reading has also been my entertainment, my relief from work and everything else. Whatever the outside pressures, I could always pick up a book and instantly be in another world. And I could stay there until I was rejuvenated and could remerge, strong again, ready to go on with new insights and ideas stolen from my betters, from those who came before. I think often and with great pleasure of a poster once seen in a children’s bookstore. An open book, a child in mid-air between the leaves, it read: “A book opens and you fall in.” So true, and not just for kids. Only books provide that complete transformation.

I did not understand then that without books I might have died from my heavy drinking, or any of the many perilous situations heavy drinking brings with it, as so many of my friends and acquaintances did…

And I certainly could never have known in the beginning the many things that would come from buying and selling books. I have probably handled millions of books, sorting, observing, judging, seeking the important and the curious and much of the detail from that process has been absorbed and become part of me, given me instincts and conferred knowledge unknown to the average reader.

Working for the Pope gave me a love of bindings (yes, you can judge a book by its cover —sometimes) and the pleasure that comes from learning the sophisticated methods used for hundreds of years to protect the sacred text. It all started with the simple protective covers the binders put on the first printed books in the fifteenth century, which were often exquisitely blindstamped with designs and symbols. Those early bindings are studied seriously now, to the point that experts can determine the styles of particular binders known to posterity only by their association with the rich patrons who commissioned them and now refer to them as “the binder of so and so”. Some people, and I am one of them, pay thousands of dollars to commission modern designs from binders who are true artists, and who, since their names are known, can receive the acclaim their talents deserve.

I came late to book illustration but am now fascinated with all aspects of it, from the simple woodcut to the sophisticated modern colour techniques, with the sequences of other techniques between, from engraving to lithography, and hand-colouring. In Victorian times, this was often done exquisitely by nineyear-old girls working in factories for sixteen hour days —a cruel indictment of human greed and lack of imagination, though it resulted in objects of great beauty, confounding our moral dilemmas even more. Everything led to our present, sophisticated means of printing colour. And the designing of books to which many people, mostly unknown to the innocent reader, have devoted their entire lives.

Few people know—and probably less care—that throughout the world small groups of aficionados devote all their free time to gouging out wood and linoleum so they can stamp pictures for their own pleasure (some actually make a living from it, but most are passionate amateurs). Others labour all night setting handtype to print, with hand-presses, some poem or saying they love, finishing with their hands and faces filthy with ink, in order to produce a single beautiful sheet with words or pictures, of no interest or use to anyone but themselves and their equally deranged friends. Everywhere there are these little groups of seemingly demented people making and worshipping the results of their passions, seeking to realize the beautiful visions their imaginations have shown them. About William Blake, obsessed with things no one else could see, his wife famously said, “I do not have much of the company of Mr. Blake. He is always in paradise.” Thought to be a lunatic then, now seen as a genius, one of the holy ones. And always, the books; first the inspiration, then attempts to inspire others; pass it on, pass it on. The wonder of it, the thrill.

And books continually offer new things, unexpected things, like looking at a woman you’ve seen a hundred times and one day seeing her in an entirely new way and falling in love. So I have done with books, I continually notice new things in familiar, previously ignored areas and the next thing I know I’m working on yet another new collection.

Early paperbacks seduced me with their wonderful, clever, commercial art—I tend to seek those that I read as a sex- and adventure-obsessed teenager in the fifties. I’ve built a collection based on the familiar, sentimental nostalgia these books induce, warm memories of my innocent naiveté (all those years ago). This went from a curious interest to a passion, then an obsession, each stage conferring increased sophistication, the parameters always widening, while more and more money was spent, with assurances to Debbie that she will make enormous profits in a few years due to my astute foresight (and she will, too).

Then postcards. After laughing for years at the silly people at flea markets and paper shows who sit for hours flipping through shoeboxes of postcards, searching for their particular passion, counties, towns, sometimes subjects, I succumbed as well. Occasionally, I would look casually for scenes from one particular place and one historical subject of personal interest, but one day, browsing, I noticed the cards that no one collects or seems to look at, the cards for the festivals—Christmas, New Year’s, and Easter—and I saw, on close examination, that those from the 1890s to 1920s or so were stunning examples of elaborate colour printing; printing far more beautiful and sophisticated than anything we see today. I began slowly buying, graduating from 25 cents and 50 cents each to $2 and $5, then buying whole albums by negotiating to get even lower individual prices. New subtleties, previously unnoticed, widened by my focus until I was buying hundreds of them knowing that, like everything one sees at flea markets, they will soon become noticeably scarce and then disappear into rarity. One day they will be worth twenty, fifty times what they are now. So goes scouting with the sophisticated scout who has the eye and the imagination to see new possibilities in ignored treasures.

“I ransack libraries and find them full of sunk treasures,” said Virginia Woolf.

Every bookseller and everyone who frequents used bookstores knows the truth of Woolf’s discoveries, for we are immersed daily in the leavings of the past and have much experience in the serendipitous discoveries awaiting anyone with a sharp eye in every bookshop.

Dealers and collectors scouting bookshops know that books can be treasures for those who can recognize the things which make a book valuable quite aside from the text. For that you need “The Eye”, the skills that all scouts nurture over many years. The great book collector Michael Sadleir once said something I repeat to myself every time I enter a bookshop, “In nature the bird who gets up earliest catches the most worms, but in book collecting the prizes fall to birds who know worms when they see them.”

There are a thousand unpursued themes where applied intelligence and discrimination can turn dross into treasure. I can’t go anywhere without new ideas and themes tunneling into my consciousness; it never gets boring. If I had time and space I would build a huge fortune, and simply wait for the world to catch up. Of course, when I tell Debra Dearlove that, she rolls her eyes. “Perhaps you’re right,” I say—smiling inside to myself because I know I’m right. But the problem is I don’t have the space or the money— and I certainly don’t have the necessary time to see my visions realized. But that has always been the fate of the visionary, just as the derision and dismissal of the naysayers has been the visionary’s reward.

But all these things I tell—of which I have thousands more examples—are not the core of it. For over fifty years living with this wonderful result of becoming addicted to reading and books (and not to ignore the magnificent irony, that after a lifetime of grappling with deadly addictions, I exult another addiction: but this one offers life, not death), I have come to realize that the greatest pleasure in it all—aside from the reading—has been the people.

All those eccentric, or just strange, people, weird and wonderful, passionate but a bit crazed, brilliant but perhaps demented—all sharing the same urge, the obsessive search for the missing book, the Holy Grail of the scout, the prize we all knew was out there somewhere, waiting for us. In the end it has been my immersion in that universe of knowledge, arcana, stories, theories, systems, plans, all fueled by the fire consuming us, all from those books which fill our lives.

I have spent much of that fifty years mixing with people of such diversity that it fills me with awe. I know people, often colleagues, who can talk knowledgeably on any period of history and often in several languages; or aspects of the sciences, or the arts, on the levels of their greatest producers. I have seen brilliance, even genius. I have had conversations with people whose knowledge or sensibilities are so much more advanced or acute than mine that I have been humbled by my inferiority—except that the humanity of these people is such that they never seem to notice their superiority. I have also known people— and not a few –whose brilliance seemed inseparable from their craziness, but who so exhilarated me that I embraced both with equal gusto.

In my years of appraising people’s archives, I have witnessed the whole inner history of people who made me proud to be a human and associated, however marginally, with such superior intellects.

I have seen greatness up close, and more often than you might think, people who have actually changed the world. I have had days when it made me feel small and insignificant and days when it spurred me to stretch my own attempts past what I know to be my limits.

I could fill a book with the lessons I’ve learned from all those appraisals. Sometimes I have been brought to tears. And it is all really just a reflection of what we humans are capable of. In the end, what most remains is the pride, pride to have been a part of it all; this great experiment we are engaged in, of being human.

So, June 15, 1967, a day of miracles perhaps—certainly for this unbeliever—where in a few minutes a consummate failure became a passionate visionary with a noble mission. Who’s to say that one moment cannot change the world? What a run I’ve had, and all from books.

-David Mason