Return to Articles / Essays

A Genre Unto Itself

Published in Canadian Notes and Queries, Number 102.

A Genre Unto Itself

Sherlockians' uniquely passionate devotion to their subject

Published in Canadian Notes and Queries, Number 102.

I thought I'd write of my all-time favourite genre, historical fiction, but decided that was inappropriate because all I'd really be doing was gushing about my favourite titles. But I'm not here to recommend my favourites, I'm supposed to be telling you how booksellers and collectors see things; I'm supposed to be giving you a different angle. So, I decided I must switch.

Thinking about historical fiction reminded me of Sherlock Holmes and his followers. I've been trying to decide if Holmes isn't the only subject that might constitute an entire genre in itself, not needing any other category to define it.

It has a central focus-The Master himself; a canon; an endless host of secondary material, from thousands of commentaries and exegeses by those acolytes-monk-like in their dlvotion to The Master-enough, arguably, for a minor religion. And it is a bit like a minor religion. The Sherlockians,

as they are known, even look and act like many beginning religions in their devotion; the only thing they lack is the hate towards non-believers so common in the latter. Not the Sherlockians, they are a gentle bunch, and booksellers tend to be very fond of them, even though they don't provide a lot of economic benefit to the trade. That's because the more devoted they become the less they need. I expect our store is the norm. We love to have them visit with their eccentric costumes and their flow of arcane trivia, but except for the odd major purchase, it's mostly just pleasure for us booksellers:

Sherlockians are mostly seeking minor scraps to fill gaps in their collections, having often beggared themselves in the early days buying the major works.

Richard Lancelyn Green, an English scholar and collector who, with John Michael Gibson, compiled the definitive bibliography of Arthur Conan Doyle, spent most of his life pursuing

Doyle's work. He regularly travelled to Canada, where we became quite fond of him. His bibliography, when published, was so complete it contained what may be the most comprehen-

sive record of any foreign author's Canadian editions that I know of. I've yet to find. an error or omission, an astonishing accomplishment. Of course, every Canadian dealer would automatically hold and offer Green any Canadian Doyle he came across. The really nice collectors, who are

also passionate, get that treatment from good dealers. Every year we, and I expect many other booksellers and Sherlockians, would receive a sumptuous Christmas card from Richard, illustrated with an appropriate Holmesian scene. On top of his book collecting and the all-consuming task of the bibliography, Richard also managed, over many years, to build a life-size model of 221 B Baker Street, Holmes' home, on the third floor of his house, replicating the entire premises so minutely described by Doyle and known well to all Sherlockians. A chapter on this can be found in

Collecting: The Passionate Pastime by Susanna Johnston and Tim Beddow (1986). A large photo of Richard's model floor accompanies the chapter. His untimely death a few years ago shocked and deeply saddened many friends in the trade and, I'm sure, Sherlockians everywhere.

That book is also a great intro- duction to the range of all collecting and the charming eccentricities of the people who do it. My favourite is on the Duke of Somewhere, a great Churchill collector. His chapter contains a photo of the Duke sitting on a couch in his Churchill room full of books and artifacts. Sitting beside the Duke is a life-size model of Churchill, his hero. But the Duke's eccentricities didn't end there. He decided that if he was going to have a Churchill room complete with effigy, he should acknowledge the man he fought and defeated, so he added a Hitler room

that also included a life-size model of the Fuhrer. The other areas of collecting portrayed in this endlessly charming book illustrate something of where passion, imagination, and slight craziness can take collectors.

Our favourite all-time Baker Street Irregular-as members of Holmes-dedicated groups refer to themselves-was probably Allen Mackler, a Midwesterner who was a particular delight. The first time he visited, many years ago, he captivated us. A short, paunchy man whose trousers always

seemed in acute danger of falling down, he bore a big lump of a growth, like half a hard-boiled egg, on his forehead. This got in the way of the tiny miner's searchlight that he wore on a strap around

his forehead. He studiously scouted the shelves-we were to find out that, in addition to the Master's canon, he had an encyclopedic knowledge of all nineteenth-century gothic novels that followed their eighteenth-century precursors. And not just Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Polidori's The Vampyre through Beckford's Vathek, Peacock's Nightmare Abbey, and, later, such near-forgotten followers as George Reynolds, "Ouida" (Maria Louise Rame) , George MacDonald, Bulwer, and a host of imitators known only to completists and booksellers, until we reach the Victorian level of Baroness Orzcy, William Le Queux, and finally the Master himself. This included thousands of paperback dime-novel spinoffs. Allen had a truly impressive compendium of scholarly knowledge. It made for some pretty arcane dinner conversations. Within an hour he had charmed us with his extremely witty and acute perceptions of Victorian novels. By. then he was addressing Debra Dearlove as "Debs," the only person I've ever seen get away with that.

Ever after that first visit, Debra and I would take Allen to dinner when he visited Toronto, where his cape and deerstalker cap would be the centre of attention for the entire restaurant while we discussed the intricacies of Gothic stories from Mrs. Radcliffe to Conan Doyle. When he died, we felt a huge hole. A couple of times we had visits from a lifelong friend of his, whom he had brought on an earlier trip. A fellow Sherlockian, he was a distinguished Midwestern surgeon who amused us with stories of his twenty-year quest to get Allen to cut off that grotesque but benign lump on his forehead. He said he offered to remove it for free (which he finally did) but Allen balked, not from

any fear, but from the inconvenience of an operation that would keep him out of the bookshops for a while. Apparently, he had inherited money, retired, and devoted his life to filling a huge house he

had in Minnesota with nineteenth-century literature and Sherlockian treasures. When he died he left this collection to the University of Minnesota. I hope they realize how lucky they were to get it. We miss his visits a lot.

These Sherlockians are everywhere in the English-speaking world (given their devotion, I'd bet in the entire world). They have meetings regularly in various cities, which explains all the dressing up.

When they meet in Toronto they almost all visit the bookstores. The Sherlockians are probably, by percentage, the greatest frequenters of bookshops of any genre collectors I've known.

Recently, Michael Dirda, who writes a regular book column in the Washington Post-and has, incidentally, written several absolutely delightful books on the wonders and pleasures of reading

(not to be missed by any book lover)-was sending me a book and declined to trust it to either of our postal systems. "I'm just going to New York for the Baker Street Irregulars. I'll give it to one of the Toronto Sherlockians, you'll get it safely," he said. Any Sherlockian would be more reliable than the postal service.

There is a whole arge group of them here in Toronto, not a surprise, Holmes being an obsession (a gentle one) everywhere. But books being below the radar for so many people, it may not be widely

known that the Toronto Public Library, along with their magnificent Osborne Collection of Children's Books, owns a Conan Doyle collection that must be one of the best in the world. Founded many, many years ago by a single donor, it was hugely augmented by the gift of another major donation from S. Tupper Bigelow, a Toronto magistrate who had a lifelong collection. And like the Osborne Collection, they also have a passionate and active group "The Friends of the Arthur Conan Doyle Collection," which holds regular lectures and meetings and raises funds to purchase additions for

the collection, sometimes very valuable ones. It is housed at the central library on Yonge Street, and if you doubt its magnificence, go in and look at what's regularly exhibited. Join it even, give them some money, maybe. They also publish a newsletter. You could even go and mix with these amusing and learned people.

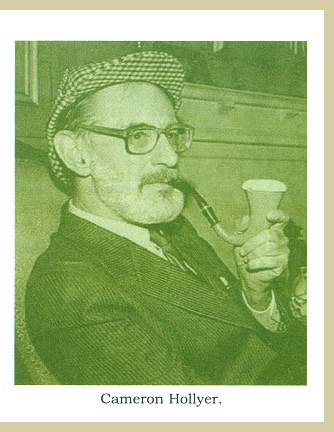

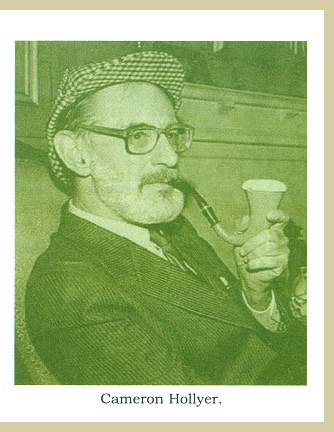

When I was starting, the Doyle / Sherlockian collection was curated by a librarian who couldn't have been more appropriate. Coincidentally, it seemed, he was almost a copy of the Basil Rathbone Holmes: very tall, gaunt, a sharply chiselled face with a hawknose. He was perfect, especially when he wore a deerstalker cap and cape, as he always did. In those days, when visitors entered the Sherlockian collection at TPL they were greeted by Sherlock Holmes himself, who would personally show them his treasures. His name was Cameron Hollyer and I think he may very well have come to believe that he really was Sherlock Holmes, only reverting to Cameron after-hours. I certainly did, and I bet half the people who knew him did too, and referred to him so. One had to remind oneself that he wasn't. I once introduced him -- by accident, but appropriately -- to a friend I had brought, "And this is Sherlock Holmes himself, in case you have any questions." It was a wonderful error

When I was starting, the Doyle / Sherlockian collection was curated by a librarian who couldn't have been more appropriate. Coincidentally, it seemed, he was almost a copy of the Basil Rathbone Holmes: very tall, gaunt, a sharply chiselled face with a hawknose. He was perfect, especially when he wore a deerstalker cap and cape, as he always did. In those days, when visitors entered the Sherlockian collection at TPL they were greeted by Sherlock Holmes himself, who would personally show them his treasures. His name was Cameron Hollyer and I think he may very well have come to believe that he really was Sherlock Holmes, only reverting to Cameron after-hours. I certainly did, and I bet half the people who knew him did too, and referred to him so. One had to remind oneself that he wasn't. I once introduced him -- by accident, but appropriately -- to a friend I had brought, "And this is Sherlock Holmes himself, in case you have any questions." It was a wonderful error

to make and Cameron loved it. It so clearly demonstrated the aim and the atmosphere of that whole make-believe universe the Sherlockians inhabit with such grace and civility.

-David Mason

Thinking about historical fiction reminded me of Sherlock Holmes and his followers. I've been trying to decide if Holmes isn't the only subject that might constitute an entire genre in itself, not needing any other category to define it.

It has a central focus-The Master himself; a canon; an endless host of secondary material, from thousands of commentaries and exegeses by those acolytes-monk-like in their dlvotion to The Master-enough, arguably, for a minor religion. And it is a bit like a minor religion. The Sherlockians,

as they are known, even look and act like many beginning religions in their devotion; the only thing they lack is the hate towards non-believers so common in the latter. Not the Sherlockians, they are a gentle bunch, and booksellers tend to be very fond of them, even though they don't provide a lot of economic benefit to the trade. That's because the more devoted they become the less they need. I expect our store is the norm. We love to have them visit with their eccentric costumes and their flow of arcane trivia, but except for the odd major purchase, it's mostly just pleasure for us booksellers:

Sherlockians are mostly seeking minor scraps to fill gaps in their collections, having often beggared themselves in the early days buying the major works.

Richard Lancelyn Green, an English scholar and collector who, with John Michael Gibson, compiled the definitive bibliography of Arthur Conan Doyle, spent most of his life pursuing

Doyle's work. He regularly travelled to Canada, where we became quite fond of him. His bibliography, when published, was so complete it contained what may be the most comprehen-

sive record of any foreign author's Canadian editions that I know of. I've yet to find. an error or omission, an astonishing accomplishment. Of course, every Canadian dealer would automatically hold and offer Green any Canadian Doyle he came across. The really nice collectors, who are

also passionate, get that treatment from good dealers. Every year we, and I expect many other booksellers and Sherlockians, would receive a sumptuous Christmas card from Richard, illustrated with an appropriate Holmesian scene. On top of his book collecting and the all-consuming task of the bibliography, Richard also managed, over many years, to build a life-size model of 221 B Baker Street, Holmes' home, on the third floor of his house, replicating the entire premises so minutely described by Doyle and known well to all Sherlockians. A chapter on this can be found in

Collecting: The Passionate Pastime by Susanna Johnston and Tim Beddow (1986). A large photo of Richard's model floor accompanies the chapter. His untimely death a few years ago shocked and deeply saddened many friends in the trade and, I'm sure, Sherlockians everywhere.

That book is also a great intro- duction to the range of all collecting and the charming eccentricities of the people who do it. My favourite is on the Duke of Somewhere, a great Churchill collector. His chapter contains a photo of the Duke sitting on a couch in his Churchill room full of books and artifacts. Sitting beside the Duke is a life-size model of Churchill, his hero. But the Duke's eccentricities didn't end there. He decided that if he was going to have a Churchill room complete with effigy, he should acknowledge the man he fought and defeated, so he added a Hitler room

that also included a life-size model of the Fuhrer. The other areas of collecting portrayed in this endlessly charming book illustrate something of where passion, imagination, and slight craziness can take collectors.

Our favourite all-time Baker Street Irregular-as members of Holmes-dedicated groups refer to themselves-was probably Allen Mackler, a Midwesterner who was a particular delight. The first time he visited, many years ago, he captivated us. A short, paunchy man whose trousers always

seemed in acute danger of falling down, he bore a big lump of a growth, like half a hard-boiled egg, on his forehead. This got in the way of the tiny miner's searchlight that he wore on a strap around

his forehead. He studiously scouted the shelves-we were to find out that, in addition to the Master's canon, he had an encyclopedic knowledge of all nineteenth-century gothic novels that followed their eighteenth-century precursors. And not just Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Polidori's The Vampyre through Beckford's Vathek, Peacock's Nightmare Abbey, and, later, such near-forgotten followers as George Reynolds, "Ouida" (Maria Louise Rame) , George MacDonald, Bulwer, and a host of imitators known only to completists and booksellers, until we reach the Victorian level of Baroness Orzcy, William Le Queux, and finally the Master himself. This included thousands of paperback dime-novel spinoffs. Allen had a truly impressive compendium of scholarly knowledge. It made for some pretty arcane dinner conversations. Within an hour he had charmed us with his extremely witty and acute perceptions of Victorian novels. By. then he was addressing Debra Dearlove as "Debs," the only person I've ever seen get away with that.

Ever after that first visit, Debra and I would take Allen to dinner when he visited Toronto, where his cape and deerstalker cap would be the centre of attention for the entire restaurant while we discussed the intricacies of Gothic stories from Mrs. Radcliffe to Conan Doyle. When he died, we felt a huge hole. A couple of times we had visits from a lifelong friend of his, whom he had brought on an earlier trip. A fellow Sherlockian, he was a distinguished Midwestern surgeon who amused us with stories of his twenty-year quest to get Allen to cut off that grotesque but benign lump on his forehead. He said he offered to remove it for free (which he finally did) but Allen balked, not from

any fear, but from the inconvenience of an operation that would keep him out of the bookshops for a while. Apparently, he had inherited money, retired, and devoted his life to filling a huge house he

had in Minnesota with nineteenth-century literature and Sherlockian treasures. When he died he left this collection to the University of Minnesota. I hope they realize how lucky they were to get it. We miss his visits a lot.

These Sherlockians are everywhere in the English-speaking world (given their devotion, I'd bet in the entire world). They have meetings regularly in various cities, which explains all the dressing up.

When they meet in Toronto they almost all visit the bookstores. The Sherlockians are probably, by percentage, the greatest frequenters of bookshops of any genre collectors I've known.

Recently, Michael Dirda, who writes a regular book column in the Washington Post-and has, incidentally, written several absolutely delightful books on the wonders and pleasures of reading

(not to be missed by any book lover)-was sending me a book and declined to trust it to either of our postal systems. "I'm just going to New York for the Baker Street Irregulars. I'll give it to one of the Toronto Sherlockians, you'll get it safely," he said. Any Sherlockian would be more reliable than the postal service.

There is a whole arge group of them here in Toronto, not a surprise, Holmes being an obsession (a gentle one) everywhere. But books being below the radar for so many people, it may not be widely

known that the Toronto Public Library, along with their magnificent Osborne Collection of Children's Books, owns a Conan Doyle collection that must be one of the best in the world. Founded many, many years ago by a single donor, it was hugely augmented by the gift of another major donation from S. Tupper Bigelow, a Toronto magistrate who had a lifelong collection. And like the Osborne Collection, they also have a passionate and active group "The Friends of the Arthur Conan Doyle Collection," which holds regular lectures and meetings and raises funds to purchase additions for

the collection, sometimes very valuable ones. It is housed at the central library on Yonge Street, and if you doubt its magnificence, go in and look at what's regularly exhibited. Join it even, give them some money, maybe. They also publish a newsletter. You could even go and mix with these amusing and learned people.

When I was starting, the Doyle / Sherlockian collection was curated by a librarian who couldn't have been more appropriate. Coincidentally, it seemed, he was almost a copy of the Basil Rathbone Holmes: very tall, gaunt, a sharply chiselled face with a hawknose. He was perfect, especially when he wore a deerstalker cap and cape, as he always did. In those days, when visitors entered the Sherlockian collection at TPL they were greeted by Sherlock Holmes himself, who would personally show them his treasures. His name was Cameron Hollyer and I think he may very well have come to believe that he really was Sherlock Holmes, only reverting to Cameron after-hours. I certainly did, and I bet half the people who knew him did too, and referred to him so. One had to remind oneself that he wasn't. I once introduced him -- by accident, but appropriately -- to a friend I had brought, "And this is Sherlock Holmes himself, in case you have any questions." It was a wonderful error

When I was starting, the Doyle / Sherlockian collection was curated by a librarian who couldn't have been more appropriate. Coincidentally, it seemed, he was almost a copy of the Basil Rathbone Holmes: very tall, gaunt, a sharply chiselled face with a hawknose. He was perfect, especially when he wore a deerstalker cap and cape, as he always did. In those days, when visitors entered the Sherlockian collection at TPL they were greeted by Sherlock Holmes himself, who would personally show them his treasures. His name was Cameron Hollyer and I think he may very well have come to believe that he really was Sherlock Holmes, only reverting to Cameron after-hours. I certainly did, and I bet half the people who knew him did too, and referred to him so. One had to remind oneself that he wasn't. I once introduced him -- by accident, but appropriately -- to a friend I had brought, "And this is Sherlock Holmes himself, in case you have any questions." It was a wonderful error to make and Cameron loved it. It so clearly demonstrated the aim and the atmosphere of that whole make-believe universe the Sherlockians inhabit with such grace and civility.

-David Mason