Collecting Games

Published in Canadian Notes and Queries, Number 95 |

As any psychiatrist will tell you, collecting is a disease of indeterminate danger, depending on its severity. Individuals with extreme versions of the disease now appear regularly on reality TV shows such as Hoarders: Buried Alive, or Packrats, all of which show us sick individuals with houses full of useless junk. Often entire rooms are rendered impassable by what the shocked viewer can see is clearly trash. The pitiable hoarder is usually seen whining that he or she desperately needs this trash for some future use, while the trash collectors — often the hoarder's children — stuff garbage bags to go to the dump.

|

These programs allow us to feel superior to these pitiable wretches while ignoring the fact that theirs is just an extreme extension of our own treasured collection of hockey cards, or empty beer bottles, or Star Wars memorabilia cluttering up the one nook our distraught, confused spouse has allotted for our personal aberration.

|

The demented hoarder is one extreme of what an eminent psychiatrist once described perfectly: “The basis of collecting is the human ability to animalize objects like the amulets and fetishes of preliterate man or the holy relics of the religionist… there is reason to believe that the true source of the habit [i.e., collecting] is the emotional state leading to a more or less perpetual attempt to surround oneself with magically potent objects.” The opposite pole of that same syndrome will be manifest in the great art and book collections housed in the world's great institutions. Before you dismiss the abject and obviously crazy hoarder, look to the Huntington, the Morgan, the Guggenheim, and, in Canada, the AGO's Thompson collection, to see a few examples of the intelligent application of that same disease.

|

|

When the editor told me this issue would focus on games I thought it would be easy for me, for all my focus as a bookseller has concentrated, as I state incessantly, on what I and every great bookseller I have known refer to as scouting, or, “The Great Game” (with apologies to the spies who coined this term). And what game could be more exciting than the search for the Missing Book, the prize, the Holy Grail of all scouts — the book found for a quarter or a dollar which the scout sells for one hundred dollars or one hundred thousand dollars. It happens, and it will happen again. For as the old scouting axiom goes, “Anything can be anywhere.” That's true, and it fuels the adventurous bookseller just as money does the poker player. Profit, and the thrill of outsmarting your opponents, motivates both these games. There are many, many sub-motives, of course — some of them even noble — but in the end we are capitalists. The profit, the reward for our combined imagination, knowledge, experience, and, not least, pure nerve, is the basis of it all. If book scouting is not a game, a Great Game, then what is? I can, and do, go on endlessly about the joys of scouting; it's what allows our work to become play.

|

So, I could write a brilliant piece about the game of collecting, but instead I've decided to tell you here about my collection of games. Because that allows me to do what always gives me enormous pleasure: to stress, yet again, the importance of the collector to the preservation of the artifacts civilization.

|

For although I've made my living for almost fifty years now selling books, I continue to see myself, first and foremost, as a collector. Even that is not quite true, for my book collecting is really the offshoot of my primary pleasure in life, my centre, the core of everything that has fuelled my life and my concerns — reading books.

|

|

I collect books because reading them has never been enough — I have always needed to possess them. That's what a collector really is, not some pseudo-sophisticated amasser of exquisite and delicate treasures, but someone who has to own the objects of their lust. Who must have them always at hand so they can invoke pleasure merely by the memories a glimpse of them brings back. If you think you're not really a collector, watch what happens when you try to weed your library. It's then you'll begin to understand the nature of your addiction.

|

|

A bookseller frequents any venue where books might be found, from the Sally Ann and Goodwill, to thrift stores, church sales, and after he or she acquires a certain sophistication, the places where the greatest treasures — if not the greatest bargains — are mostly to be found: the antiquarian bookstore. My collection of games started in flea markets, where I still go regularly in search of books, but where, more often than not, I end up taking home bizarre things that no presumably sane person would want to own. Somehow one finds oneself taking home weird things, often sneaking them in, for fear one's mate will see that day's treasures as the final straw, the proof that their mate is demented, and that they had best escape while they still can.

|

|

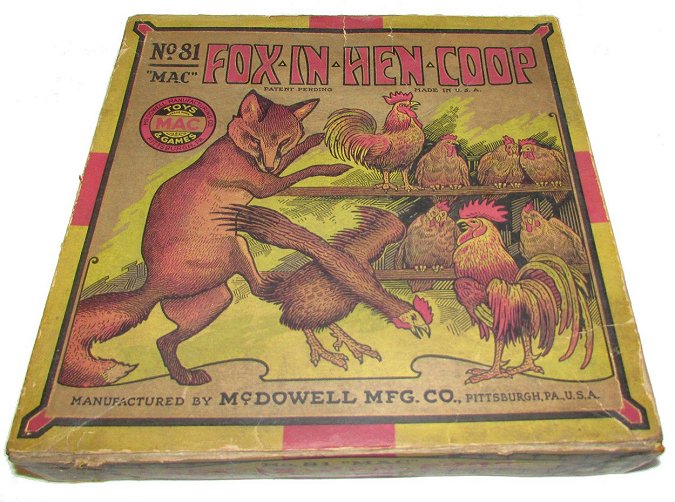

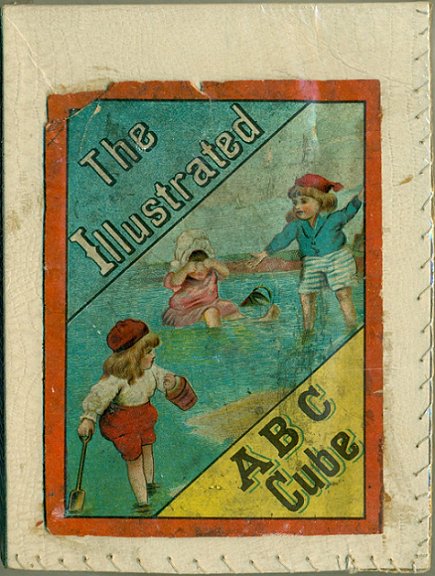

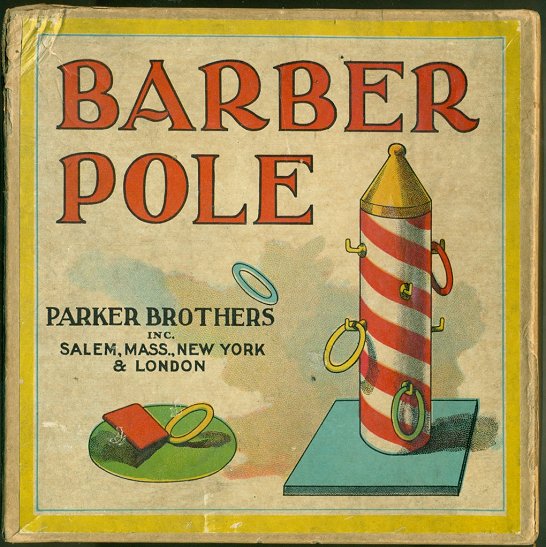

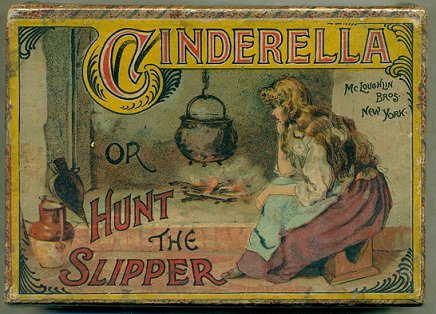

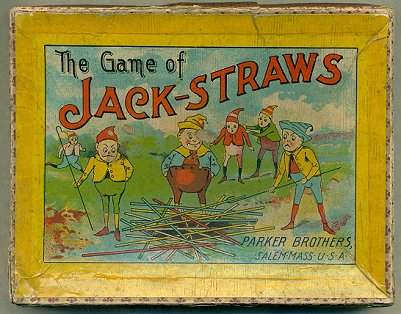

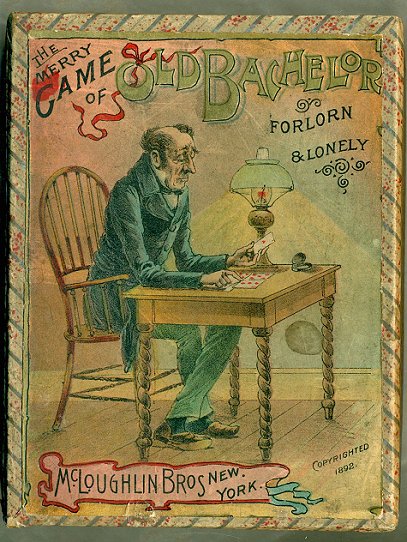

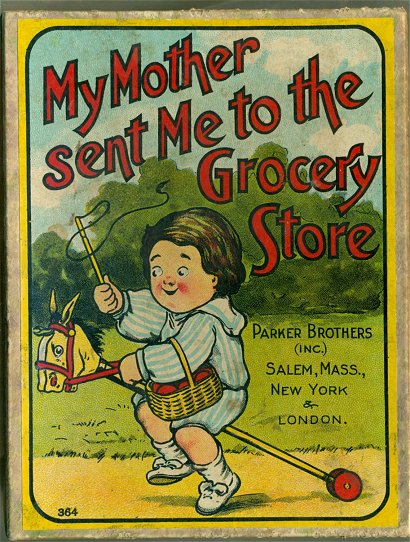

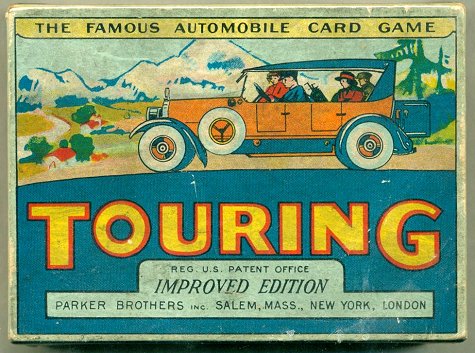

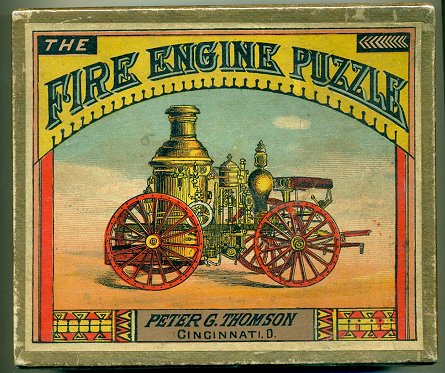

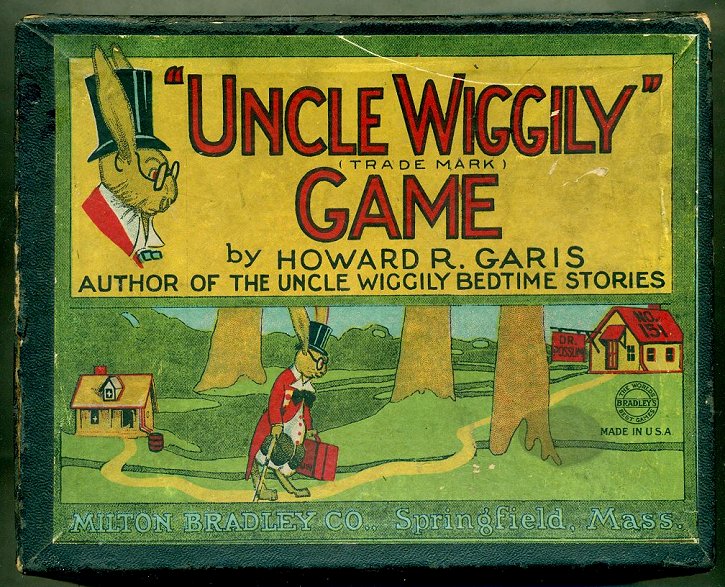

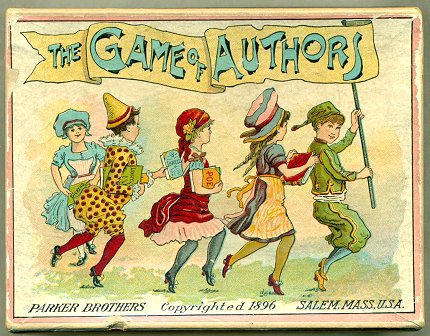

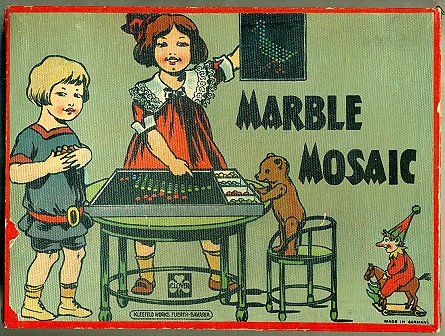

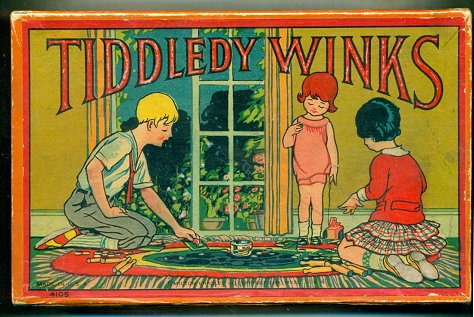

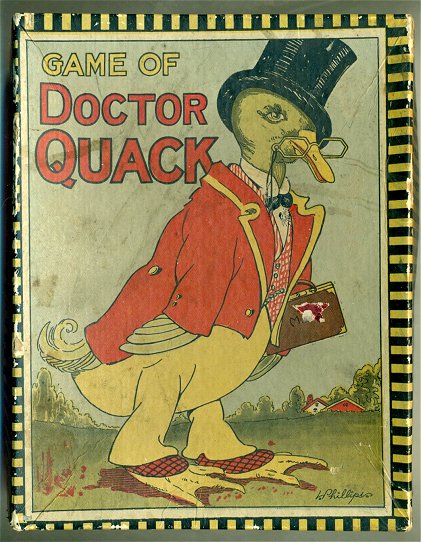

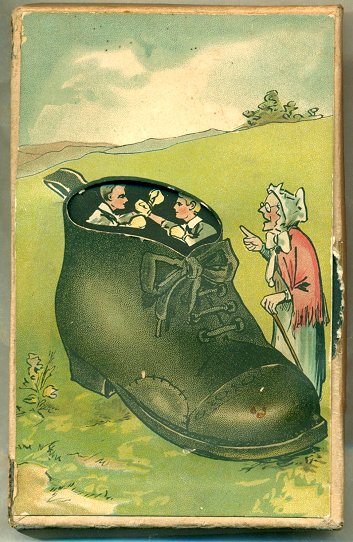

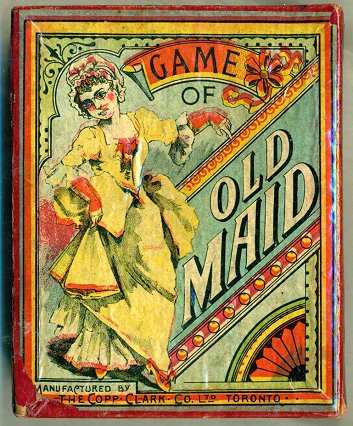

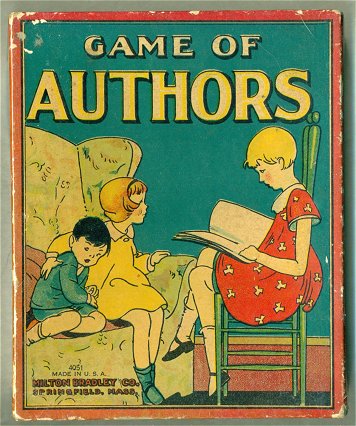

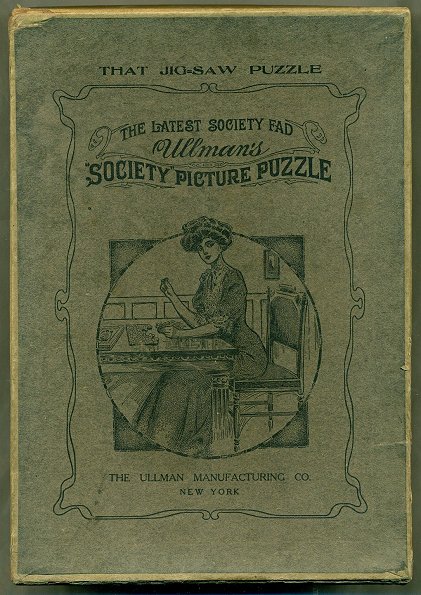

My first game was both justified and completely sane. Indeed, it demanded to be bought. It was a small cardboard box with a colourful top label announcing it as, “The Uncle Wiggly Game.” I was caught on two levels. Uncle Wiggly, one of the heroes of my childhood reading, was already one of my passionate book collections. This game was a necessary adjunct. I had also long been fascinated by the cardboard boxes from the 1870s to the 1920s containing everything from medicines to women's accessories to tools and gadgets, and had been casually buying them for quite a while. I liked the covers for their clever, often very colourful advertising, and I liked the perishable nature of cardboard as opposed to, say, tin boxes, which are less prone to destruction. I did not consider these boxes, of which I had many, as a collection. Mostly they were bought casually, in passing, as cheap fun.

|

It's only when the person who has bought a lot of things begins to see certain patterns, and decides to logically and intelligently expand those patterns that a collection takes form. At any given time I have several areas of casual interest. Sometimes I'll buy a bunch of new additions, other times ignore the same things, depending on my mood. Usually a point is reached where the casual interest becomes a collection, but sometimes I lose interest and the incipient collection is dispersed, back to the flea market.

|

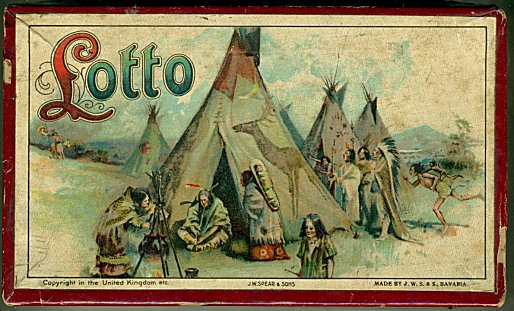

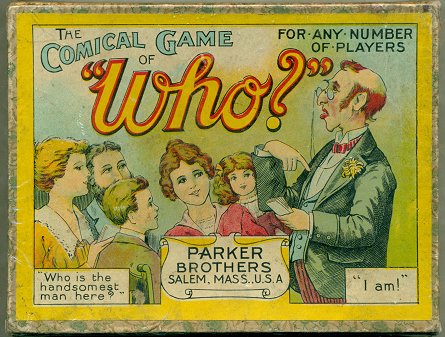

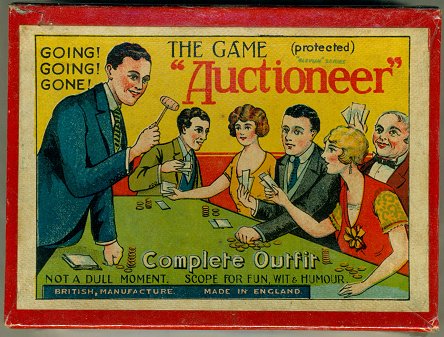

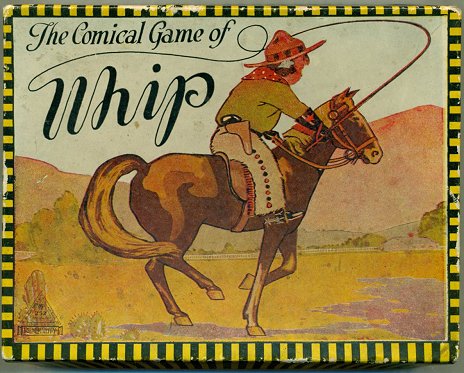

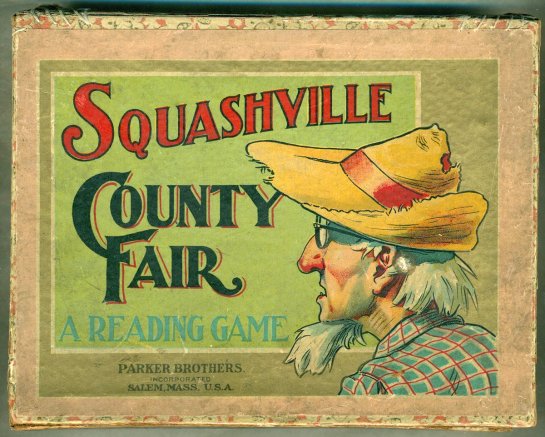

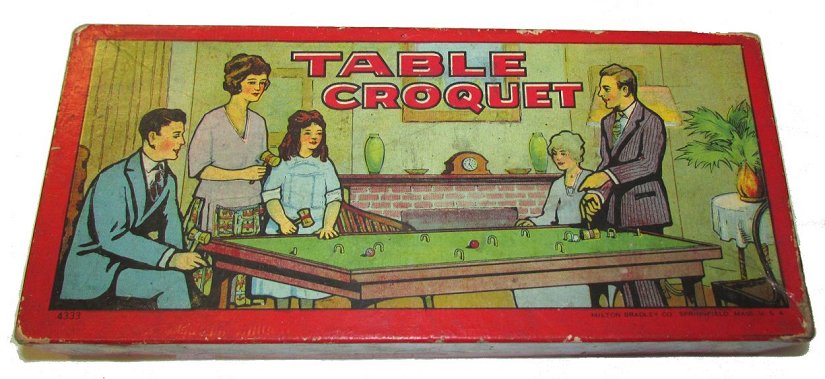

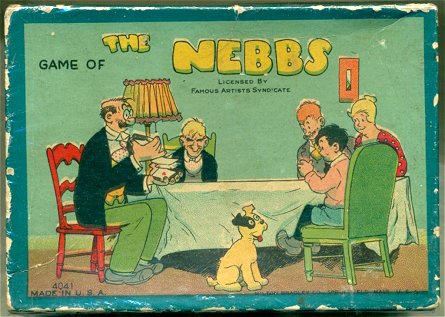

“The Uncle Wiggly” game delighted me, so when I saw another game in a similarly nice cardboard box with a colourful period label, I bought it, too. This seemed to pose no new danger until a year or so later, when I found that I had bought a half-dozen more, all different, but all cardboard-boxed games, and I realized I had succumbed to yet another addiction. Still, as I wasn't paying more than ten or twenty dollars each for them, it didn't seem serious. Later, it became one hundred to two hundred dollars.

|

But that was all right too, for I had, as I always do, followed the primary rule of all collecting and the primary justification for all collectors. The first demand is condition: the rule is, if you buy things in fine-to-perfect condition you'll always have a way out. This first rule is sometimes the hardest to learn, but once learned properly it will serve you well. Every collector has regrets about the things they bought with defects, or in less than fine condition. The defective item is never a bargain, as we all learn. The second point, the perhaps sick, even demented, justification, goes like this: “When I'm dead Debbie (my partner) will get a lot of money for these things and will realize that I was way ahead of my time in vision and will finally realize that I was not the deranged sicko she said I was, but the brilliant visionary I knew myself to be.”

Whatever the truth of it, this justification works well — at least for me. Perhaps it is best not to investigate its veracity too deeply, best to just use it, as I do regularly. Still, if you only buy fine things there is some chance it could be true.

|

So, I've been doing this for fifteen or twenty years without thinking much about it. It's only now, having pulled out the accessible games for pictures that I see I have formed a reasonably valuable collection.

|

Following the condition rule I have probably rejected nineteen games for every one I've bought. And since these games were used, and cardboard is fragile, I have often spent more money having my bookbinder repair the more important boxes than I ever would have considered paying for a whole game during the first few years, after Uncle Wiggly brought me down to perdition.

|

Looking at what I have casually, but so pleasurably amassed, I see I have spent a fair hunk of money overall.

|

But Debbie probably won't get rich from it, for I will probably donate it to the Toronto Public Library's Osborne Collection, to which I owe so much. The Osborne has a very good collection of games, as well as one of the greatest collections of children's books in the world, and I like the idea of paying back some of my lifelong debt to public libraries and feeling I'm part of such a wonderful endeavor.

|

|

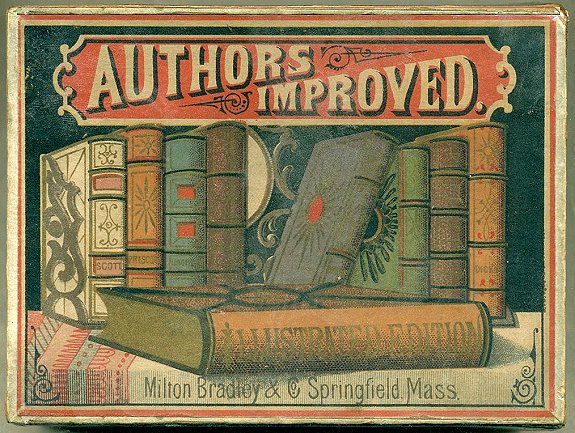

Naturally there have been some offshoots, detours from the precise path I started with. Looking for one thing, you often find something similar which appeals. While looking for card games I discovered playing cards, and then a whole art deco scene related mostly to cards and bridge. So I started buying cards. But only decks with art deco designs. And that led to bridge counters from the thirties and forties, also with lovely art deco designs. Playing cards — except, of course, early ones, which are very expensive — are ludicrously cheap still. And with these cards, as always when I explore a new area, I have discovered incredible examples of brilliant twentieth-century art that I previously never even noticed.

|

Early games can be extremely expensive. I have bought some outside the cardboard box imperative, some wooden ones, some cloth-covered boxes. Why not? I make the rules and the first rule is that I buy what pleases me.

|

While I have a fair number of games, both English and North American, after around 1930 I find they lack the essence of the period I so love. The rule there is that I buy them only if they're very cheap; that way I can store them away from the core collection, which remains uncontaminated by modernism. But, of course, I know in my collector's soul that, in a later generation, they'll be very valuable as well. Debbie will certainly become quite wealthy because of my vision and imagination, I tell myself. And then she'll be sorry she made fun of me. I'll be vindicated even though it will be too late for her to make amends.

|

In closing, I think I should say something about playing these games. Some idiots lacking all comprehension like to believe that collectors don't read their books; true book collectors do, just as real game collectors play their games. I cannot illustrate here one of my favourite games, which is a bit outside what I'm describing anyway. Debbie gave it to me one birthday, early in our relationship. I still have it but can't find it, sadly. It was called something like “The Wolf and the Piggy,” and consisted of a costume of wolf's ears and long snout, and paws that I wore as gloves (I was the wolf). The piggy part was ears, a pink snout, and gloves in the shape of trotters (Deb was the piggy, being pinker than me). She and I would don our costumes and play very interesting games — in private let it be said. We had a lot of fun, and if I could find the game this article might have photos of us dressed up in our game uniforms. Perhaps that's what aroused my initial interest in games. It's nice to think so.

|

-David Mason