Bibliographical Journeys:

The Bookseller As Saviour

Published in Canadian Notes and Queries, Number 98.

As I have recounted elsewhere, after the introduction to the wonders of history and literature I received when I stumbled, by accident, on I, Claudius as a fifteenyear-old, I found myself exploring those fascinating subjects in ever widening areas.

It was at that time that I began some serious reading, no longer just for the pleasure I got from the stories, but as a learning process, which I continue to do with the same passion as I did then. Much of it came from my discovery of the Penguin Classics, but, as with all broad and haphazard study, there were many detours – one book inevitably leading to another. The young seek answers to the eternal dilemmas, as they should, so it is hardly strange that I began to explore the major religious books – the Koran, the Bhagavad Gita, books on Buddhism, especially Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and the I Ching, which I found fascinating and consulted regularly. I read the Bible too, but having rejected the religion I was born into (I still remember my reaction to St. Augustine’s Confessions: fascination, in the early parts, where he explored debauchery and the pleasures of the flesh, followed by boredom after his conversion, where all he did was tell others not to enjoy what he’d had enough of), my explorations there were mainly in the Old Testament, and mostly from a literary viewpoint.

It was at that time that I began some serious reading, no longer just for the pleasure I got from the stories, but as a learning process, which I continue to do with the same passion as I did then. Much of it came from my discovery of the Penguin Classics, but, as with all broad and haphazard study, there were many detours – one book inevitably leading to another. The young seek answers to the eternal dilemmas, as they should, so it is hardly strange that I began to explore the major religious books – the Koran, the Bhagavad Gita, books on Buddhism, especially Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and the I Ching, which I found fascinating and consulted regularly. I read the Bible too, but having rejected the religion I was born into (I still remember my reaction to St. Augustine’s Confessions: fascination, in the early parts, where he explored debauchery and the pleasures of the flesh, followed by boredom after his conversion, where all he did was tell others not to enjoy what he’d had enough of), my explorations there were mainly in the Old Testament, and mostly from a literary viewpoint.

But a few years into my quest my reading became influenced by another factor – the inaccessibility of English books in Spain, where I then lived. I was forced to read the books I had, or could scrounge, although when a local friend gave me Garcia Lorca’s plays in Spanish, I began to learn and read in that beautiful language. Later, my Spanish friends were openly skeptical when I told them I was reading Don Quixote in the original, for Cervantes’ Spanish was as different from modern Spanish as English is over the same period. It was my fractured, self-styled grammar and my atrocious accent that caused this skepticism; those friends were unaware that anyone who has spent a lifetime with books understands far more than their speaking ability or vocabulary could indicate. Still, at best I got the meaning but missed the subtleties that make for great literature, and I never did finish that attempt.

I did read Darwin’s Origin of Species cover to cover, although I expect most biology students only read the argument, which is in the last thirty pages. The fascinating details of the diversity of flora and fauna also gave me the first hint that maybe I had been stupid to abandon a proper education. That thought still nags from time to time.

I read Ulysses then too, finding that the incomprehensible parts became clearer if I read aloud. (Years later a friend told me that his device, when confused, was to sing it, which I think is a much cleverer solution than mine.)

I read books I’d never have read simply because I didn’t have anything else to read. I’m very glad now that I did – I only wish I’d had Gibbon with me, which I now will die not having read in spite of having started it at least a couple of dozen times.

I read books I’d never have read simply because I didn’t have anything else to read. I’m very glad now that I did – I only wish I’d had Gibbon with me, which I now will die not having read in spite of having started it at least a couple of dozen times.

I began sending lists of books I wanted to my long-suffering mother. These lists, made up of mentions culled from my reading of other books by authors I liked, were eclectic. My mother would take my list when she went downtown to Eaton’s and so could easily visit Burnill’s Bookshop nearby at Yonge and King, the very store where, ten years earlier, I had purchased my first new book. Years later I worked out that Gordon Norman, the man who would become one of my early mentors in bookselling, was the manager of Burnill’s in that period and almost certainly would have been the person to whom my mother would have presented my list. So I don’t believe it’s presumptuous to conclude that this man was a reading mentor before he became my bookselling one. Gordon did what a good bookseller does, he used my list as an indication of the areas I was exploring, and when he didn’t have a specific book I wanted, substituted what he considered appropriate alternatives instead. And it worked. When we spoke about it years later, he didn’t remember my mother – booksellers get a surprising number of mothers with lists – but he agreed that it almost certainly would have been he fielding my lists. I thanked him profusely for that help.

This unfocused reading led me along some very strange paths and I will recount here perhaps my favorite, if convoluted, example of where such lucky coincidence can lead.

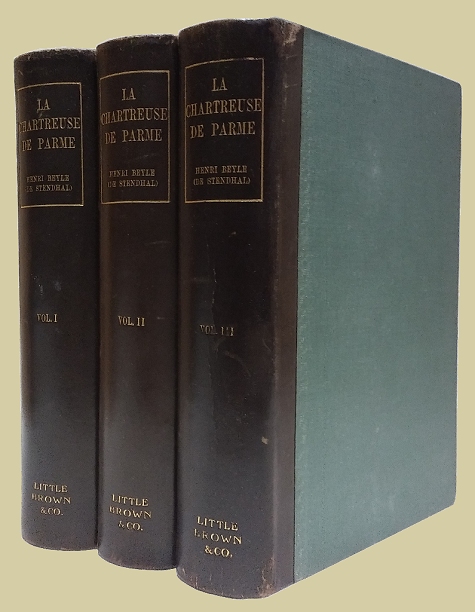

A passing mention somewhere led me to ask for Stendhal’s The Red and the Black. Burnill’s didn’t have it in stock right then so Gordon substituted The Charterhouse of Parma, a stunning book that I came to consider the greatest romantic novel ever written, certainly my favourite. (Later I learned that Somerset Maugham shared my opinion.) It contains accounts of not just one but two (!) great love affairs – one between two passionate youngsters my age at the time and the other between two old people (old then meaning in their late thirties or early forties – forty is ancient when you’re twenty). I take it as mark of great personal character that even then I found the love of the two “old” people much richer and much more interesting than the insatiable passion of the young couple. I think only a true romantic could view the affairs of the world in such a manner at such a young age. I still cite Count Mosca as an example of pure courage in matters of love (indeed, I consider him to be Stendhal’s alter ego).

Reading The Charterhouse of Parma led me to request anything by Stendhal, which resulted in my receiving next an extraordinary book – extraordinary on several levels – called A Roman Journal. It was ostensibly a travel book. A combination of a history and an exploration of Rome, it described the city’s architectural wonders and church art interspersed with salacious and fascinating details of various Roman intrigues, particularly papal history. Here we discover the astounding excesses of the Borgias, but also read of countless other despicable popes not far behind the Borgia clan in their sinister and very unChristian machinations.

After that, for years to come I sought out and read works on the history of the papacy. Coincidentally, my work as a bookbinder included binding a series on Spanish-Jesuit relations, so I was also reading about the exploits of Church representatives amongst the natives of South America. Years later I read some accounts of Jesuit-Native relations in Canada. In both parts of our hemisphere it was hard to tell whose practices were more heinous; the natives who tortured their captives to death for sport, or those ignorant, fanatical Christians who burned people at the stake in their attempts to impose their religion on them. Read Brian Moore’s The Robe if you doubt that.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of A Roman Journal is the fact, pointed out by Stendhal’s translator Haakon Chevalier in his introduction, that Stendhal wrote such incredible descriptions of the churches and buildings of Rome without having ever been there. To him, it was hackwork taken on after the friend who’d been commissioned to write it fell ill. Stendhal, poor and needy, took on the job for money. That he could have produced a masterpiece by applying his incredible imagination to information culled from books seems almost unbelievable. It led my reading into many other areas. When I later became a bookseller, I began buying copies of A Roman Journal to give to friends. For some reason the original English translation is very scarce in hardcover, I’ve bought every copy of both editions I’ve located in forty years, but only three of them were hardcover and even the paperback is now scarce. It also led to my lifelong devotion to Stendhal, all of whose work is in my library.

But the ironies continue. For some reason when I finally did locate The Red and the Black I never could get more than halfway through it. I try periodically and always bog down. The inescapable irony is that had I received it on first request I probably never would have read Stendhal – which is the equivalent of never meeting one of the great loves of one’s life, I think.

And I’m not done yet. Now for some bibliographical details.

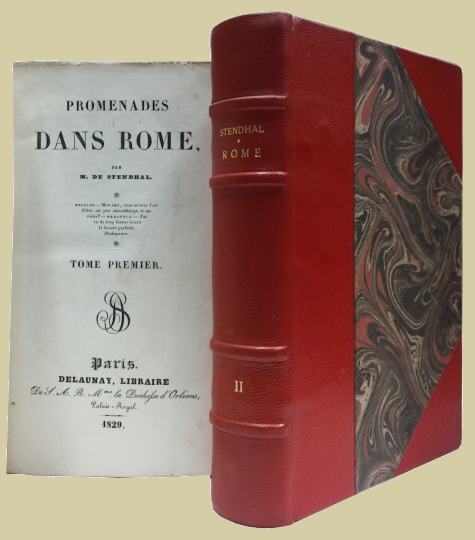

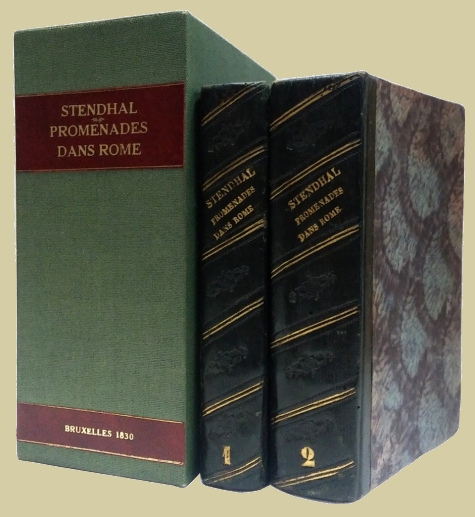

I have the Charterhouse in my library in the first edition in English – which was published very late (New York 1895, three volumes) (writer’s take note). It is forty-three years after Stendhal’s death that the English-speaking world begins to catch up; it can happen to you too. Take heart!) – and in several other editions and subsequent translations. I also have it in a very early French edition – the second, I think. The first is a very expensive book, as it should be. I never expected to ever see – or at least at any price I could pay – any early French editions of Promenades dans Rome (the French title of A Roman Journal) until several years ago, when I found the first Belgian edition (Brussels 1830, two volumes) in an American dealer’s catalogue at what I considered the ludicrously low price of $250. I ordered and got it; I was elated. So, I thought, at least I will own an early edition, if not the true first. But a couple of years ago the true first edition (Paris 1829, two volumes) appeared in a small book auction in Toronto. I knew no one in Toronto would look at that book the way I did and I determined that whatever price it realized, I would buy it, even if it reached its market value, which would be around four or five thousand dollars, I was pretty sure that it wouldn’t approach that price in Toronto. Furthermore, I knew that my only probable competition in the Toronto trade would be my most despised colleague, a man I haven’t spoken to in over ten years, since he sued me for libel (I consider being sued by this man as one of the high points of my career).

And sure enough, when it was auctioned, it was he who bid against me, making it even tastier when I bought it for around $1,400.

And sure enough, when it was auctioned, it was he who bid against me, making it even tastier when I bought it for around $1,400.

Had I been on even formal speaking terms with this man I would have given myself the pleasure of twisting the knife by informing him that I was prepared to pay four times as much as I had. Dealers hate to be told they dropped out of the bidding too soon, and even more so when their enemies triumph.

And I get even more pleasure from these recollections when I think of Stendhal’s great dedication to his readers, “To the Happy Few.” For this could equally apply to all book collectors, who are often dismissed with derision by their own families. But truly, to those of us who understand what books really confer, book collectors are indeed amongst “the Happy Few.”

And so all these wonderful, varied permutations came from one bookseller using his own judgment and sending a substitute book. It’s as good an example as you’ll ever find, it seems to me, of booksellers’ importance to civilization.

-David Mason