Apples and Oranges.

Books versus movies

Published in Canadian Notes and Queries, Number 99.

The world can be divided into two classes of people; those who say, "No, I haven't seen it but I read the book," and those who say, "Great movie, some day I mean to read the book." The connections between books and movies are so intricate and entangled that no conversation about one can go on for long without drawing in the other.

The antiquarian book trade, especially for those who specialize in Modern Firsts, is full of books that have been made into movies. Collectors, including me, are strongly drawn to owning a first edition of a book whose movie adaption has special significance for them. I have known dealers who specialized in selling these books and I've done a fair bit of that myself without it being more than a passing interest. This has led to many discussions - often lively and passionate disputes - with fans of both genres. Book people tend to have strong views about movies, based on having read the book first. I've been studying the phenomenon for years trying to figure out why some movies don't work for me and I've concluded it's most often not the changes Hollywood makes to the book for commercial purposes, but the casting that offends me. I may be, for instance, one of the very few people who didn't like Lawrence of Arabia because I could never see Peter O'Toole as Lawrence. I knew the real Lawrence too well, and had deep regard for him, from Seven Pillars of Wisdom and the many biographical accounts I've read. There are countless more examples. Often, readers are certain that the producers of the movie missed the essential point of the book in the process of making the film.

The antiquarian book trade, especially for those who specialize in Modern Firsts, is full of books that have been made into movies. Collectors, including me, are strongly drawn to owning a first edition of a book whose movie adaption has special significance for them. I have known dealers who specialized in selling these books and I've done a fair bit of that myself without it being more than a passing interest. This has led to many discussions - often lively and passionate disputes - with fans of both genres. Book people tend to have strong views about movies, based on having read the book first. I've been studying the phenomenon for years trying to figure out why some movies don't work for me and I've concluded it's most often not the changes Hollywood makes to the book for commercial purposes, but the casting that offends me. I may be, for instance, one of the very few people who didn't like Lawrence of Arabia because I could never see Peter O'Toole as Lawrence. I knew the real Lawrence too well, and had deep regard for him, from Seven Pillars of Wisdom and the many biographical accounts I've read. There are countless more examples. Often, readers are certain that the producers of the movie missed the essential point of the book in the process of making the film. With all the intricate connections between the two art forms - which are much more different than casual comparison might suppose, for reading is active, and watching a movie is passive, as McLuhan so aptly put it - there are many comparisons that cause the fans of both genres to argue which was superior. This becomes even more heated with people who love both forms, for there is no real right or wrong. Those discussions never end with any resolution, but they certainly are fun.

Book people almost always prefer the book, and some, myself included, often dislike a movie because it offends a private universe based on their emotional view of the book. By my observation, these are the main reasons why book readers dislike certain movies: so-and-so wasn't my idea of the protagonist; the book made you feel those things, the movie missed the point; that milieu isn't really like that; real life problems are not so stark; real whatevers would never act like that - ad infinitum. With a book, the reader constructs his or her own imaginary world. When the movie tampers with that world the reader is offended. I know I am. A movie, on the other hand, demands a passive acceptance of the director's, writer's, and actor's views of the story. A debate about the relative merits of a film is usually endless, entertaining, and futile: disputes based on the emotional response of its disputants are never swayed by reason. They certainly won't be changed by another, equally emotional, opinion.

The antiquarian market has seen an increase, in recent years, in the dealing of original scripts in various versions, often written or re-written by well-known writers whose novels are already widely collected. Sometimes this will be an adaption of an author's novel by a screenwriter - sometimes the tenth adaption - sometimes the author's own screen treatment of his own book, or even original scripts by that author.

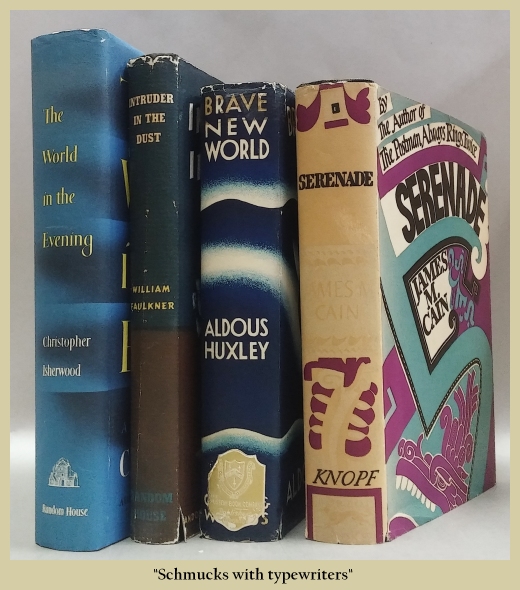

There is also a pretty significant literature about the famous writers who were lured to Hollywood in the thirties, and later, for money. This includes writers like Fitzgerald, Faulkner, James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler; and the British emigres like Huxley and Isherwood. There are many interesting biographies and memoirs full of anecdotes of the insults and humiliations that important writers suffered at the hands of vulgar, ignorant producers, whose common view of them was "Schmucks with typewriters."

There is one antiquarian firm, Baltimore's Royal Books, which is becoming quite prominent now, that specializes principally in film and its connections to both books and photography. They issue regular catalogues containing first editions of books, but primarily scripts, stills, posters, lobby cards, even publicity packets, often personalized by the various people who worked on the film. The prices asked by this firm were originally shocking - even to old pros like me, whose skepticism was kept in abeyance until the third or fourth catalogue. At that point, it was precisely my professionalism that told me that these prices were not insanely outrageous, for there would be no third and fourth catalogue if the earlier offerings had failed to sell. This firm has now established itself as the foremost specialist in the field. Others will no doubt be copying their style - and their prices - once another genre of collecting becomes established. Collectors, especially those who would like to own some of their offerings, will slowly pass from outraged denigration ("They're nuts, I'd never pay that!"), to sheepish acceptance, and will buy their offerings using the collector's usual justification, "If I'd pay that so will someone else someday -maybe more if I live long enough." Such rationales, of course, are really just an excuse to do what you wanted to do in the first place.

Another prominent dealer recently offered a film script written by Jim Harrison, my favourite American author. I was outraged at the $2,000 price tag and was thankful that its ludicrousness saved me from a sick self-indulgence I know only too well. And yet after a night of reflection I found myself ordering it the next morning, and was further outraged - and disappointed - to find it had already been sold. It took only one night for a criminal price to become an acceptable price. And, as all collectors know, it doesn't take much longer for that same price to become a bargain price in the future.

One of my favourite book/movie comparisons occurred some years ago preceding the International Festival of Authors in Toronto. At a cocktail party I had a long talk with W. P. Kinsella, the author of Shoeless Joe, a book beloved of baseball fans, and which was made into one of the few movies I can think of that compares favourably with the original source. I had to be a bit cautious about what I spoke about with Kinsella, because he had been very friendly with my nemesis, Bill Hoffer, the Vancouver bookseller who had published some of Kinsella's chapbooks. I also have a serious collection of the work of Evelyn Lau, whom I consider one of the most naturally talented young writers I've encountered. She and Kinsella had had an affair that ended badly, in public recriminations and threatened lawsuits. I also knew that Kinsella - who seemed to be cordially disliked by most of the other Canadian writers, and had a reputation for irascibility - had been hit by a car in his driveway, been concussed, and had undergone some sort of personality transformation. Apparently, he was no longer writing, but spent all his time playing Scrabble and travelling to tournaments for the latter around North America. (Note: That seems to have changed. Kinsella published another book just before his recent death.)

He was wandering the room, apparently unconcerned by his being ignored by the other writers. When I went up and introduced myself I found him very agreeable, and we spent over an hour discussing baseball and literature. I began by asking him if he had approved of Field of Dreams, the movie they made from Shoeless Joe. The filmmakers had disguised the writer, who in the book is Salinger, by renaming him Terence Mann and having him portrayed by the black actor James Earl Jones, perhaps to avoid Salinger's notorious propensity to sue at any perceived infringement on his privacy.

"Yes," said Kinsella, "I did like the movie."

"I watch it around once a year and reread the book as well," I said. "It makes me cry every time."

"It does me too," he said. "What part makes you cry?"

"At the end when he's playing catch with his father," I said. "That's my son's favourite part too. What part makes you cry?" I inquired.

Kinsella said, "The part where the little girl is choking just as Burt Lancaster's youthful player is getting his first chance to bat in the Bigs." When Lancaster's character sees the accident, he leaves the field and chooses to cross the line, becoming again the elderly doctor, his last chance to capture his dreams having been outweighed by his duty to medicine.

We were both silent for a bit, maybe fighting the urge to cry again.

So emotional did I find this encounter that I'm not sure if I asked Kinsella if he had seen to it that Salinger got a copy of the book and, if so, if there had been a response. I can't imagine not asking such an obvious question, but I have no recollection of having done so.

Anyway, I had a wonderful time and now I find myself, on my yearly viewing of Field of Dreams, tearing up in two places.

Sometimes those comparative discussions enhance both art forms.

-David Mason